Marina Abramović at the Intersection of Performance Art and Fashion

Words by Lena Sophie Eckgold

Edited by Rachel Hambly and Bailey Tolentino

Performance artist Marina Abramović, born in Belgrade, Serbia (former Yugoslavia) in 1946, has been defining what performance art and body art can be for over six decades. From the very beginning, she has pushed her body to extreme limits: she has cut herself, burned herself, starved herself, exhausted herself, and exposed herself. Pain, violence, endurance, and vulnerability are recurring themes in her performances. When the body itself becomes the medium, the question of its second skin – clothing – inevitably arises. What role does fabric play when art is so radically physical? And how does this connect to the world of fashion?

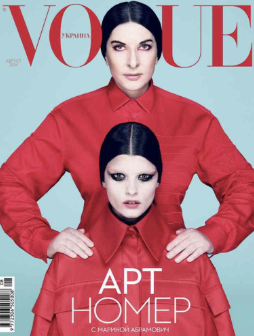

Today, Abramović is not only the self-proclaimed ‘grandmother of performance art,’ but also a fashion icon. She sits in the front rows at fashion shows by Prada, Versace, Jil Sander, MM6, Ferragamo, Fendi, and Dolce & Gabbana; was the face of a campaign for Massimo Dutti; appears regularly at the Met Gala; has collaborated with Givenchy; and has now graced over sixty magazine covers, including Vogue. Her performative wardrobe and her presence in the modeling world increasingly blur the boundaries between performance art and fashion.

Marina Abramović and Crystal Renn for Vogue Ukraine, August 2014

However, her affinity for fashion was by no means inevitable. Although ‘the relationship to fashion started a long, long time ago’ and she ‘always liked fashion,’ Abramović recalls she was ‘ashamed to love fashion.’ Growing up in communist Belgrade— shaped by a strict upbringing and an authoritarian aesthetic – both her parents were Yugoslavian ‘national heroes’ and wore uniforms throughout their entire lives. Clothing was therefore political, a visible sign of discipline. Abramović was not allowed to buy ‘anything fancy or anything [she] liked’ and recalls in her autobiography how shameful it was even to feel the desire for beautiful clothes.

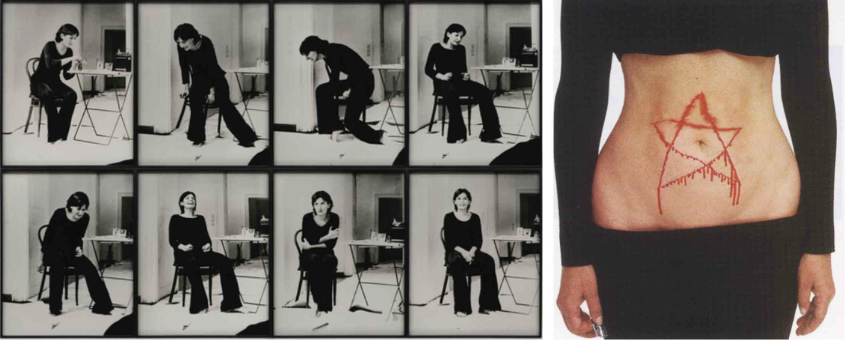

Her early performances reflect precisely that: Abramović appeared in minimalist outfits – simple black or white trousers, white shirts – but often completely naked, as a radical turn towards the body as the absolute centre of art. In the art scene of the early 1970s, fashion was considered nothing short of a betrayal of artistic integrity. ‘For an artist to wear red lipstick or beautiful clothes was absolutely unacceptable. It meant you were trying too hard and you weren’t a good artist,’ she says in retrospect.

Marina Abramović: Rhythm 2, 1974 (left), Marina Abramović: Lips of Thomas, 1975 (right)

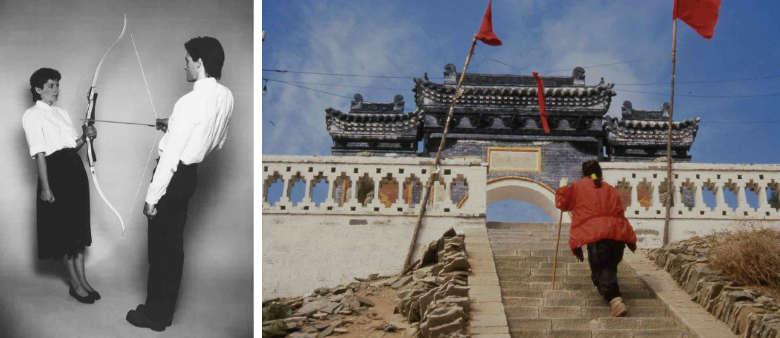

In the 1980s, Abramović made several collaborative art pieces with Ulay, her long-time artistic and life partner. In these pieces, they both wore similarly androgynous, minimalist clothing that underscored their idea of the ‘third unity,’ an artistic fusion of two bodies. They lived in their car for a time, adopting an ascetic lifestyle and buying clothes only from second-hand shops or knitting them themselves from heavy wool.

With The Lovers (1988), Abramović began to understand, for the first time, the emotional memory carried by materials and clothing. In this performance, Abramović and Ulay walked the Great Wall of China from opposite ends to meet in the middle, then separated for good. For this, she wore durable leather shoes with thick soles. They became ‘a part of [her] body,’ she says in an interview. In her autobiography, she describes: ‘The moment I put them on, I have this rush of memories of everything I've been through, how hard it is to be an artist.’ Here it becomes clear: functional clothing is essential for endurance performances – yet the physical intensity makes it a carrier of memories.

Marina Abramović and Ulay: Rest Energy, 1980 (left), Marina Abramović: The Lovers, 1988 (right)

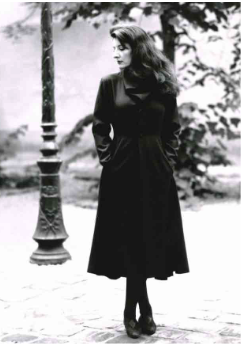

After her emotional separation from Ulay, but with her professional success on the rise, Abramović sold three works to the Centre Pompidou – and for the first time in her life was able to buy a piece of clothing she truly wanted. She bought a pair of trousers, an asymmetrically designed jacket and a white blouse, a single pleat jutting out geometrically, from Yohji Yamamoto. ‘I still have the clothes,’ she writes in her autobiography, ‘I went out and felt this incredible pleasure. Paris was smiling at me and everything was wonderful.’ Here, for the first time, clothing became something more than just functional for her: it became self-confidence, a sense of identity and femininity, a space for refuge and expression.

Abramović’s first fashion photoshoot, dressed in Yohji Yamamoto, Paris, 1989

In her three-month performance The Artist Is Present (2010), in which visitors could view her as she sat in the atrium during MoMA’s opening hours, Abramović linked these experiences with the question of functionality. In her autobiography, she describes how she had a dress made, ‘floor-length and woven in cashmere and wool, to keep [her] warm.’ It came in three colours: blue for calm, red for energy, and white for purity. Here, clothing was directly linked to emotion, becoming emotionally charged. ‘The dress was like a house that I inhabited,’ she writes. While she gave herself entirely to the performance physically, the clothing became her place of retreat.

Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present (2010)

Abramović developed a special connection to the fashion world through her long-standing friendship with Riccardo Tisci, former creative director of Givenchy (2005–2017) and later Burberry (2018). The day after The Artist Is Present ended, MoMA and Givenchy organized a joint celebration for which Tisci designed a long black dress and a coat made of snakeskin – a mythically charged reference to Medusa that translated Abramović's unwavering gaze during the performance into couture, as it were. Tisci also asked her to reinterpret a Givenchy haute couture dress – Abramović washed it in a waterfall in Laos until the fabric dissolved, literally transforming fashion into performance, in a gesture that ritualistically cleansed and dematerialised the garment. In 2011, Abramović and Tisci posed as a modern Madonna and Child for the photographic project The Contract, in which the connection between (performance) art, fashion, and Christian faith is pushed to an iconographically provocative extreme.

Marina Abramović and Riccardo Tisci: The Contract (2011)

This collaboration continued throughout the following years: for her production of Boléro at the Opéra Garnier (2013), Tisci created lace-trimmed, skeleton-like bodysuits for the dancers. In 2016, he invited her to art-direct the Givenchy Spring/Summer 2016 show in New York on 11 September – a respectful, meditative tribute to the anniversary of 9/11.

Boléro at the Opéra Garnier (2013) (left), Givenchy, SS16, New York (right)

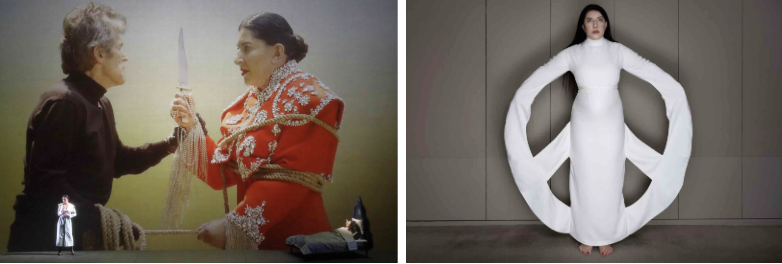

For the opera project Seven Deaths of Maria Callas (2020), Tisci designed all the costumes in which Abramović, alongside Willem Dafoe, died as seven opera heroines in cinematic sequences. And most recently, he created a bespoke white dress with a prominent peace symbol for her 2024 Glastonbury performance – inevitably the most political statement in their interdisciplinary collaboration.

Seven Deaths of Maria Callas (2020) (left), Marina Abramović in Peace Dress designed by Riccardo Tisci, 2024 (right)

Looking back on her decades-long relationship with fashion, however, Abramović is also critical of the industry. ‘Fashion is in a state of crisis,’ she says, referring to the endless rotation of the same designers between the big houses, the lack of genuine innovation, and the emptiness that arises when fashion only produces content. She points to the revolutionary power of early designers such as Vivienne Westwood and the role of Tisci, who naturally placed queer communities at the centre of couture. What Abramović calls for is less a trend than it is an attitude – fashion that carries meaning, that shows courage, that transforms the body rather than decorating it.

Her own relationship to fashion embodies precisely this understanding: for her, clothing is, among other things, political and symbolic, shaped by her communist childhood; functional in her endurance performances; emotional as a carrier of memories; ritual-like; performative in works such as The Artist Is Present; spiritual in the photo project The Contract – and, last but not least, a means of self-awareness as an artist and a woman. Abramović frames her own trajectory as: ‘So we cross all these lines now between what is art and what is fashion.’

Yet whether she practices this understanding without contradictions remains debatable: Abramović consistently stages herself as a brand, and her increasing engagement with luxury houses has led critics to accuse her of capitalist self-mythologising and the commodification of performance art. Despite such tensions, one thing can certainly be said: her position demonstrates how art and fashion nourish each other and ultimately merge.