Dressed for Power: A History of Masculine Influence in Womenswear

Words by Kate Hilditch

Edited by Rachel Hambly and Bailey Tolentino

If you were to see a woman walking down the street today in a tailored blazer or a tie, it likely would not cause a reaction. However, this acceptance took a long time to come to fruition. Historically, women were bound by strict social rules dictating what they could wear: typically limited to dresses, underskirts, and restrictive corsets that constrained both movement and independence. A shift began in the 1850s, when women’s rights activist Amelia Bloomer challenged these conventions. She advocated for abandoning heavy corsets and petticoats in favor of wide, loose-fitting trousers worn beneath skirts. These garments, later known as bloomers, became a symbol of early feminist reform and were inspired by traditional Turkish fashion. They represented one of the first public challenges to restrictive dress codes for women.

Change accelerated further during the 1920s and the period surrounding the First World War. As women entered the workforce in large numbers and gained the right to vote, practicality in clothing became essential. Women began adopting looser, more functional garments traditionally associated with menswear. This shift symbolized a new freedom, both social and physical, as women were no longer confined to clothing that restricted movement. During this decade, women increasingly wore collared shirts, Oxford shoes, and trousers. Masculine clothing also gained traction in artistic spaces; performers such as Gwen Lally became well known for their androgynous, or even masculine dress, both on and off stage, often playing male roles in Shakespearean productions.

One of the most influential figures of this era was Coco Chanel. A defining fashion icon of the 1920s, Chanel rejected overtly traditional femininity and championed comfort, simplicity, and menswear-inspired design. She introduced women to elegant suits, tweed blazers, striped tops, and relaxed knitwear, and she herself frequently wore trousers. Despite the growing visibility of women in pants, popularized by figures such as Katharine Hepburn, trousers were still considered socially acceptable for women only in limited situations, such as sports.

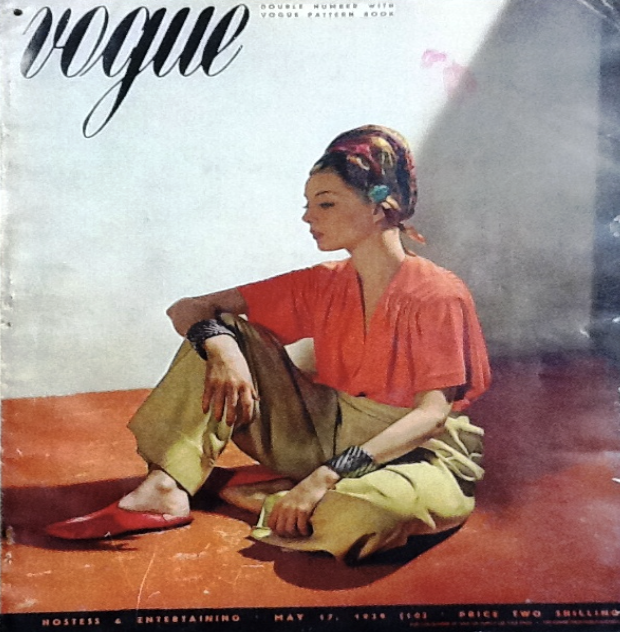

A significant milestone came in 1939, when Vogue featured a woman wearing trousers on its May cover. The magazine described the look by stating, “Our new slacks are irreproachably masculine in their tailoring, but women have made them entirely their own by the colours in which they order them, and the accessories they add.” This moment reflected a growing cultural acceptance of women adopting masculine silhouettes.

The social advancements of the 1960s, including the Equal Pay movement and the Civil Rights Act, further reshaped women’s roles in society and in fashion. In 1961, Audrey Hepburn appeared in Breakfast at Tiffany’s wearing black capri trousers, reinforcing the idea that women could embody elegance without traditional femininity. As a global style icon, Hepburn’s influence encouraged many women to embrace more practical, streamlined clothing.

During the 1980s, the rise of the power suit marked another defining moment. Characterized by tailored jackets, strong shoulder pads, and knee-length skirts, the power suit symbolized women’s growing presence in professional and corporate spaces. Broad shoulders and structured silhouettes intentionally minimized the emphasis on traditional feminine curves, reflecting authority and ambition rather than ornamentation.

Today, traditionally masculine clothing plays a significant role in women’s fashion. Ties, waistcoats, oversized blazers, and tailored suits regularly appear in both street style and high-fashion collections. Celebrities frequently wear power suits on the red carpet, and designers continue to challenge traditional gender boundaries through their work. This ongoing evolution demonstrates that fashion is not confined to a single gender: it is innovative, expressive, and constantly redefining what empowerment can look like.